We tend to think of Santa Claus as something inherited. A figure passed down quietly through generations, like a family recipe or an old song everyone somehow knows by heart. Red suit, white beard, warm eyes; an image that feels timeless, and therefore unquestioned. But memory, as it turns out, is rarely accidental. In marketing, while attention and performance often take center stage, branding works on a deeper layer: shaping what feels familiar, trustworthy, and inevitable over time. Few examples show this more clearly than Coca-Cola’s long relationship with Santa Claus, not as an advertising character, but as a cultural symbol that no longer feels designed at all.

Before Branding Took Hold: When Santa Claus Was Still Unsettled

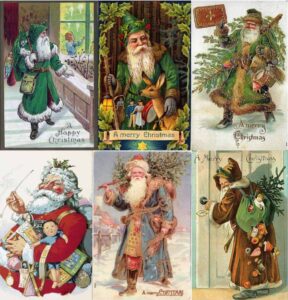

In fact, Santa Claus is not just a made-up character. He originated from Saint Nicholas, a bishop who lived in Turkey during the 4th century and was famous for his generosity. When Dutch immigrants brought the figure of “Sinterklaas” to New York in the 17th century, the name gradually changed to “Santa Claus.” By the 19th century, stories even began describing him as a jolly and chubby man. However, even though he had a name and a personality, he still lacked a single, unified look.

Across regions and decades, he appeared in many forms, sometimes thin, sometimes heavy, sometimes stern, sometimes playful, and occasionally even unsettling. He was recognizable, but not yet agreed upon.

This matters because strong brands rarely invent meaning from nothing. They enter moments where meaning is still fluid, where symbols are culturally available but emotionally unresolved. Santa Claus, at the time, was exactly that: present everywhere, but anchored nowhere. A character without a settled narrative or a common emotional center.

Source: Public domain

Coca-Cola’s Strategic Choice: Branding as Selection, Not Invention

Source: Public domain

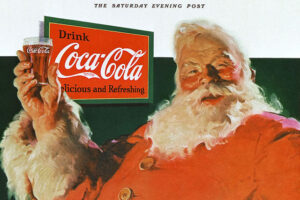

Coca-Cola did not invent Santa Claus. What they did was far more restrained, and far more strategic. They chose one interpretation and committed to it.

This Santa was warm rather than distant, human rather than mythical. Gentle, approachable, and grounded in everyday life – someone who belonged in living rooms, not legends. Once the choice was made, Coca-Cola repeated this image consistently, year after year, across decades. No reinvention. No reinterpretation. Just continuity.

Over time, interpretation gave way to recognition. Recognition hardened into expectation. This is where branding truly begins, and where marketing often ends. Marketing persuades and activates; branding stabilizes and settles. Marketing seeks attention; branding designs memory.

Why This Was Branding, Not Just Marketing Campaigns

If Coca-Cola’s use of Santa had been driven purely by marketing objectives, it would have focused on short-term outcomes: seasonal sales, promotional urgency, campaign performance. Instead, the company invested in brand identity over time.

They didn’t explain Santa or justify his presence. They allowed the image to exist repeatedly until it stopped feeling like communication altogether. Eventually, Coca-Cola no longer appeared as an advertiser, but as part of the holiday itself.

They didn’t try to convince people to drink soda in winter, a difficult proposition by any standard. Instead, they aligned themselves with how winter felt: warmth, generosity, ritual, and comfort. One approach pushes messages outward, the other embeds meaning inward.

The Psychology Behind Brand Familiarity and Cultural Memory

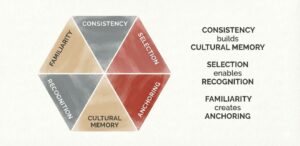

From a psychological and linguistic perspective, this strategy reflects a clear understanding of how meaning forms. Meaning doesn’t emerge from isolated exposure, but from patterns: repetition within a stable emotional context.

When an image appears consistently in the same emotional environment, the brain stops processing it as external information and begins storing it as part of the environment itself. At that point, the brand is no longer communicating. It is inhabiting.

This is why Coca-Cola’s Santa feels obvious today. He is processed not as a brand creation, but as cultural knowledge. And cultural knowledge, once established, is rarely questioned or traced back to its origin.

Source: Public domain

When Successful Branding Disappears

The paradox of effective branding is that the better it works, the less visible it becomes. Most people cannot recall a specific Coca-Cola Christmas advertisement, nor do they remember slogans or campaign copy.

What they remember instead is a feeling – warmth, generosity, a sense of ritual – and a Santa Claus who feels inseparable from it. Many even believe this version of Santa has always existed. That belief is not a misunderstanding, it is the outcome.

When branding succeeds at a cultural level, authorship disappears. The brand dissolves into cultural memory and is defended not as a corporate construct, but as tradition itself.

Source: Public domain

What Modern Brands Often Get Wrong About Branding

Many modern brands pursue relevance through constant reinvention: new identities, shifting tones of voice, refreshed values introduced year after year. But memory does not work that way.

Trust cannot be built with something that keeps reintroducing itself. Cultural memory requires patience, consistency, and restraint. Coca-Cola understood that meaning fractures when symbols change too often.

In a marketing landscape obsessed with speed, novelty, and optimization, they chose continuity. And continuity, over time, is what turns symbols into anchors rather than noise.

Conclusion

When we talk about the importance of branding in marketing, we are not simply talking about logos, colors, or visuals. We are talking about the ability to shape what is remembered, and what no longer needs explanation.

The Santa Claus we recognize today feels timeless, almost inevitable. That timelessness was designed. Branding matters not because it speaks louder, but because it stays consistent long enough to be believed. When done well, it teaches the world what to remember quietly, patiently, and without asking for credit.